Those working in the health, transportation, education, and household sectors or at night or in remote areas are highly susceptible to violence and abuseJakarta (ANTARA) - Workplace sexual harassment is among the most challenging and insidious issues since victims are oftentimes in a vulnerable position, fearing their careers wrecked or also jobs lost if they muster courage to rock the boat.

Nearly one-third of women in G20 nations have faced harassment at work but most suffer in silence (Women at Work Poll, 2015).

Indonesia was the only Asian country in the G20 that cited flexible working as the top challenge for women at the workplace, with 41 percent of females citing it as their biggest concern.

In fact, a mere one percent of Indonesian women came clean about been harassed at work.

Sexual harassment is a form of sexual violence. Harassment is a product of a gender system dominated by masculinity and patriarchism that usually has to do with sexual practices.

Harassment has a broad dimension -- it can occur from the time of recruitment or while working daily, or from verbal to physical -- which results in the degradation of one's working conditions.

In the world of work, harassment can be categorized into two main forms: quid pro quo and hostile environment. The first occurs when one party compels the other to accept a sexual offer by offering certain rewards or threats, such as promotions, a salary hike, and if declined, the worker will be fired.

The second form pertains to efforts directed at making working conditions inhospitable, for instance, irrelevant communication outside working hours and bullying.

Following this, Alvin Nicola initiated to build a platform in Indonesia that offers a space for survivors of sexual harassment at workplace to share their stories anonymously.

Alvin believes that speaking up about experiences is part of the resistance. Stories need to be told, deconstructed, reconstructed—not simply heard—in order to avoid reifying existing unhelpful or oppressive stories.

As a social initiative, the Never Okay Project is active in the non-litigation sector.

We focus on strengthening community capacity and anti-sexual harassment commitments at work institutions, Never Okay Project Coordinator Nicola affirmed.

The Never Okay Project does not specifically offer legal assistance. Alternatively, in the event of a request, they bridge such needs with the relevant legal aid agencies.

From the results of The Never Okay Project's online survey (2018), some 94 percent of the 1,240 respondents had experienced sexual harassment at work. Female workers dominate the victim count. Along with the stories mashed to their website, the characteristics and modus operandi of harassment proved to be quite broad-ranging, from verbal to rape.

In the non-litigation process, The Never Okay Project assisted two cases: Mrs. Nuril and Amel (The Workers Social Security Agency / BPJS Ketenagakerjaan).

"We centralize data and information and then disseminate it back to the public as a campaign and awareness tool. During the legal process, we inform about the atmosphere of the trial and the development of cases in order to garner public support," Nicola explained.

In the context of sexual harassment, two main supporting factors are weak law enforcement and a culture of harassment normalization.

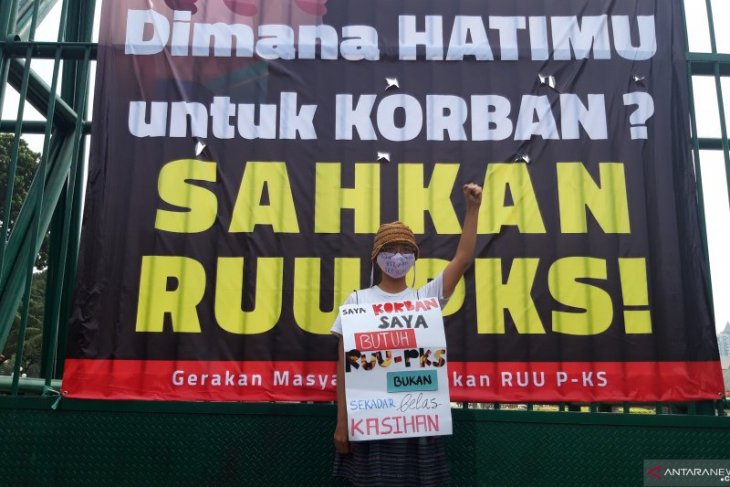

A void of an anti-harassment law exists until now since no specific regulations governing sexual harassment in the world of work are yet in place. Indonesia is the only country in the ASEAN that does not have this legal instrument that also demonstrates a low commitment to pass the sexual violence bill (RUU PKS).

Furthermore, the government also appears reluctant to ratify ILO Convention Number 190 that has been ratified to encourage the commitment of the state to eliminate violence and harassment in the world of work.

As a result, companies and institutions are indeed reluctant to develop a regulation that is not regulated by the state's obligations and sanctions, particularly if it is considered potentially detrimental to the company and has no impact on profits.

In addition, surveys and stories bring to light a lasting tendency to blame the victims. Nearly 50 percent more victims are reluctant to report for fear of being blamed by the perpetrators, who are usually the victims' superiors.

The fragility of social spaces through support groups and trade unions is also an important aspect that is lost in the talk on harassment.

The female workers are also sucked into a vicious circle that constantly harms them. They face a dual burden since they become victims, both while working in the office or after returning home.

"We often find stories where they have to struggle to avoid harassment in their offices and also to avoid violence in households," Nicola remarked.

This circle of legal vacuum and awareness of equality must be cut by the state and companies.

"Based on our experience in partnership with 34 companies/institutions, we see a tendency to lack awareness of the importance of building an anti-harassment system and culture. We always suggest three approaches: starting with research, developing regulations and sanctions, and strengthening trade unions. The main modality of this achievement actually lies in the commitment of all stakeholders in opening healthy discussion spaces and encouraging a culture of mutual respect between workers," Nicola stated.

ILO Convention No. 190

The International Labour Organization (ILO) issued Convention No. 190 of 2019 on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work.

The convention, adopted at the 108th ILO session in Geneva, Switzerland, June 21, 2019, contained various provisions, including recognizing the right of all to a world of work that is free from violence and harassment, including gender-based violence and harassment of women.

The ILO encourages the application of ILO Convention No.190 on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the world of work, one of which aims to ensure the protection of workers regardless of a contract status of employment.

The convention's focus on inclusiveness is of paramount importance, thereby translating to the fact that anyone, who works, will be protected regardless of the contract status of employment, according to the ILO's senior advisor, Tim De Meyer.

De Meyer affirmed that apprentices, volunteers, job seekers, and people, who exercise authority as employers, are entitled to receiving protection under ILO Convention No.190.

This is also applicable to the public and private sectors, the formal and informal economic sectors, as well as urban and rural areas.

De Meyer drew focus to the fact that several groups of workers in certain sectors, positions, and work arrangements were also especially vulnerable to violence and harassment.

Those working in the health, transportation, education, and household sectors or at night or in remote areas are highly susceptible to violence and abuse, he stated.

In addition, gender-based violence and harassment is one of the key areas of focus of ILO Convention No. 190, with an approach that also considers third parties, such as clients, customers, service providers, and patients.

This is since they can be victims or perpetrators too, De Meyer pointed out.

Furthermore, the convention on the elimination of violence and harassment in the world of work takes into account the impact of domestic violence in the world of work.

The definition of violence and harassment in the world of work is stipulated in ILO Convention No.190 on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work.

The convention did not differentiate between the definition of violence and harassment. The definition of violence and harassment included physical torture, verbal abuse, beatings, sexual harassment, threats, and stalking, he pointed out.

He noted that the convention also took into account the conditions and ways of working in the modern world, where work activities were oftentimes not conducted in physical workplaces, such as offices.

Hence, ILO Convention No. 190 also covers communication related to work, including those that might occur through information and communication technology.

De Meyer stated that the convention provides a clear framework of action for efforts to shape the future of the dignified world of work.

This convention also offers an opportunity to shape the future of the world of work that is free from all forms of violence and harassment, he remarked.

In the absence of a state commitment set forth in a regulation, it will become increasingly difficult to put an end to violence and sexual harassment experienced by women in the world of work.

The country's commitment is of utmost importance to encourage every company and institution to create a dignified world of work.

Through the presence of a regulation on the elimination of violence and harassment in the world of work, victims are brave enough to speak up.

Related news: Sexual harassment is often complex and undercover: ILO

Related news: Minister points to persistent grim participation of female workforce

EDITED BY INE

Editor: Fardah Assegaf

Copyright © ANTARA 2019