A young girl in college had to bury her dreams of being a literature graduate as she had been raped by a famous poet at one night after the two met at a campus’ event. The girl kept silent for months for fears and ashamed, but she decided to speak up when people found out there was a life inside her womb. But, to speak the truth would never be easy for her. A lifetime trauma stalled her words to be clearly heard by her friends, family members, lawyers, and the worst was the law enforcement.The girl and the poet might be mere fictitious characters or an unverified testimony of an unidentified victim, but the story of the rape itself was a possible reality every woman has to deal with anytime, anywhere worldwide, including here in Indonesia.

Despite of the legal actions she pursued to seek for justice, the law enforcement dismissed her lawsuit not just once or twice, but thrice. The poet could get away from the rape charge, and he still managed to hold exhibitions, publish a book, and continue to thrive as a respected figure in a literary world. Meanwhile, the girl had to suffer as she would never be able to scrap off the bad memories of someone-who-forced-himself-on-top-of-her for some reasons she would never understand.

UN Women’s Facts and Figures estimated that “35 percent of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner (not including sexual harassment) at some points in their lives”.

According to the UN body, some 15 million adolescent girls aged between 15 and 19 years around the world have also experienced forced sexual intercourse or other sexual assaults. The ugliest truth of the UN Women’s factsheets might be the part that shows only one percent of the millions of survivors had ever reported seeking professional help.

Meanwhile, in Indonesia, the number of cases of sexual violence in the country had nearly doubled for at least three years, from 259,150 reports in 2016 to 406,178 in 2018, the National Commission for Eradication of Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) estimated in its 2019 Annual Note or CATAHU.

The annual report also indicated last year that 71 percent of the violence had occurred in women’s private lives, some of which include marital rape and domestic violence, while 28 percent of the incidents of sexual violence, such as rape, sexual assault, and harassment, were experienced by women in public spaces. However, the number of victims may be higher as the annual note’s records are based on the lawsuits received by the district/city courts in Indonesia and reports compiled by the commission, as well as civil society groups.

One story about rape is one story too many.Indonesia’s legal system, mainly its criminal code law, has imposed stringent sanctions on sexual offenders, as they can be imprisoned for five to 15 years and also be liable to face capital punishment if the victims suffered fatal injuries and were underaged. Last month, the Bangkalan District Court in East Java Province had dropped a death penalty to five rapists/murderers.

Join #GenerationEquality and stand with us to end sexual violence against women and girls. #orangetheworld #16days pic.twitter.com/oG775cjnp3

— UN Women (@UN_Women) November 22, 2019

Despite a possible capital punishment and a near 15-year jail term, the existing law had failed to dissuade future perpetrators, as women in the country continue to experience sexual violence. The question is: “what’s wrong?” Some may answer the nature of sexual violence has been beyond the legal aspect, as it was a matter of culture, a rape culture.

Rape culture

A group of feminist-sociologist/anthropologists in the United States around the 1970s had first coined a term of rape culture that was later dubbed as the main root for the pervasive sexual violence against women.

In its popular definition, rape culture is a male dominated-constructed view that allows any forms of sexual violence to be justified and normalized. In the meantime, according to UN Women, "rape culture is the social environment that allows sexual violence to be normalized and justified, fueled by the persistent gender inequalities and attitudes about gender and sexuality".

Believe women. Don’t excuse perpetrators. Don’t joke about gender-based violence.For instance, in terms of the response to the victims of sexual assaults, rape culture may appear in some expressions, such as "boys will be boys"; "women say no, but they actually mean yes"; "she wears mini skirt"; "she walks alone at night"; "she asks for it"; or "she was drunk”.

There is something each one of us can do to end rape culture. #GenerationEquality #orangetheworld #16days pic.twitter.com/XMujYTyd2m

— UN Women (@UN_Women) November 22, 2019

Due to these presumptions and judgments, most victims sometimes choose to stay silent rather than file reports with the law enforcement, as the social cost of being subjects of critics, accusations, and embarrassment by the society were high. Starting from the presumptions and denigrating expressions directed at the victims, the rape culture continues to flourish in the community by shaping the laws, basic norms, traditions, and also languages that undermine women falling victims to sexual assault.

For women in Indonesia, safe access to report sexual assault remains a subject of doubt, with some past cases delivering a clear message that victims may end up in jail for reporting their stories to law enforcement. A case of Baiq Nuril Maknun, a female teacher in West Nusa Tenggara Province, who reported her school principal over some unlawful sexual calls, could be a sound example on how a victim would suffer more than the perpetrator.

Instead of being protected by the law, Nuril, a victim, had turned into a defamation convict after a judge found her guilty for sharing records of sexual calls made by the school principal, Muslim. Following the verdict, Nuril had to face a five-month jail term and had been fined Rp500 million. In the meantime, Muslim, a sexual offender, was acquitted of the charge as the police returned Nuril's lawsuit over lack of evidence.

Nuril's case has drawn nationwide attention, and she managed to obtain President Joko Widodo’s pardon this year.

However, the story of her struggle sends across a clear message that the rape culture may have already penetrated the country's legal system, and people should fight it, including by advocating the anti-sexual violence or anti-rape bill (RUU-PKS) to be passed into law.

Anti-Sexual Violence Bill

Since its first hearing in 2017, members of the House of Representatives had yet to reach conclusions to agree on some articles of the anti-sexual bill. Some articles that spark debate include the definition of sexual violence and the nine forms of sexual assaults that comprise sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, forced contraception, forced abortion, rape/marital rape, forced marriage, forced prostitution, sexual slavery, and sexual exploitation.

According to its opponents, the bill had veered far from the religious values embedded in the lives of most communities in the country, as they accused some articles as being “too liberal” and will not be suitable for people in Indonesia.

However, for its supporters, the bill has covered a wide and deep range of multi-faceted forms of sexual violence, as well as the proper punishment and restitution to the victim. The bill also ensures safe and secure protection for victims to report sexual assault to the law enforcement apparatus without fears of being avenged and intimidated by perpetrators.

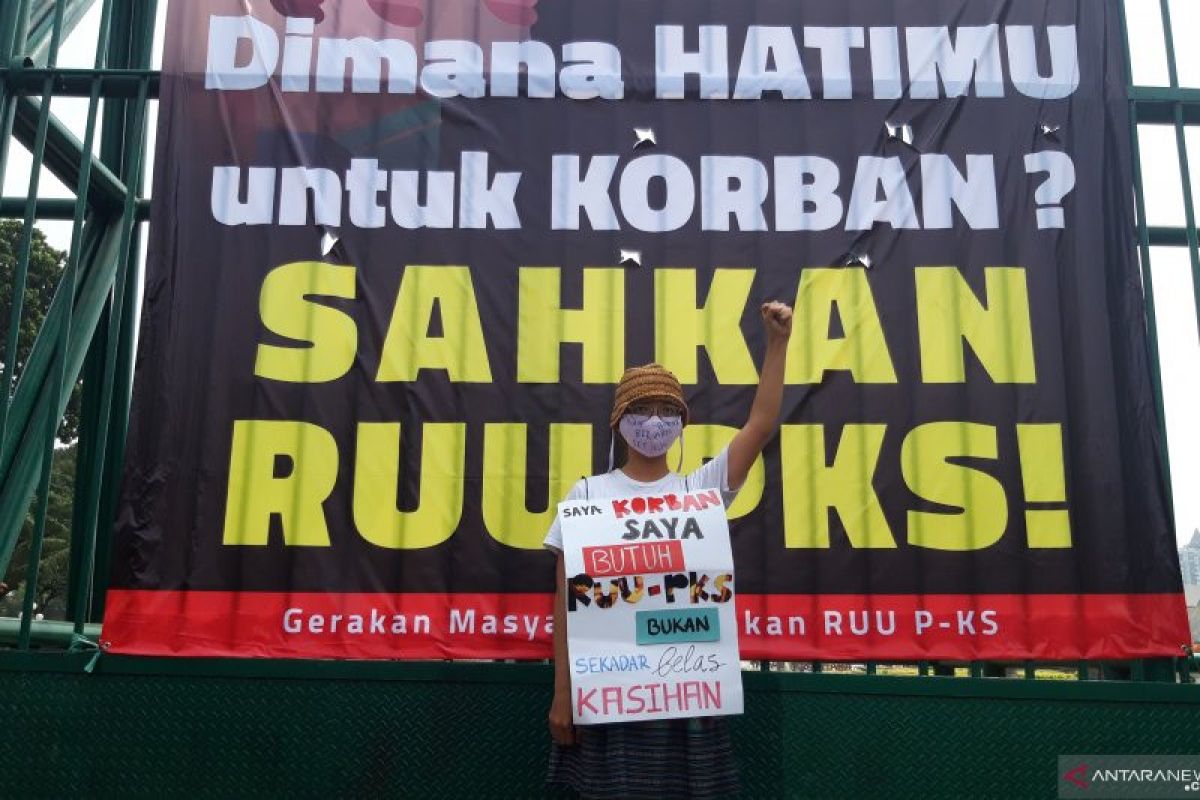

Debates and rhetoric over the bill continue until this day. However, the future of the anti-sexual violence bill hangs in the balance, as the newly elected lawmakers at the House of Representatives told the press last month that they must await the controversial revised version of the criminal code bill (RKUHP) to be passed into law.

At this point, the only question people need to ask lawmakers is whether they care about the current and future victims of sexual violence, as the final call lies in the political will among lawmakers.

Despite lengthy deliberations and debates over the bill, the only serious question the lawmakers must answer is whether they want to stop the rape culture in the country or continue the insanity.

If the answer is yes, they will instantly pass the bill since as simpler as it sounds: "any forms of sexual violence is wrong. Pass the bill!"

Related news: Strong commitment paramount to combating workplace sexual harassment

Related news: Team Baiq Nuril delivers amnesty petition to government

EDITED BY INE

Editor: Fardah Assegaf

Copyright © ANTARA 2019