At a depth of 10,045 meters, they peered through the small windows of the deep-sea submersible DSV Limiting Factor and watched their surroundings move as if in slow motion.

Vescovo was then surprised when he caught sight of two black eyes staring at them only to realize they belonged to a stuffed teddy bear.

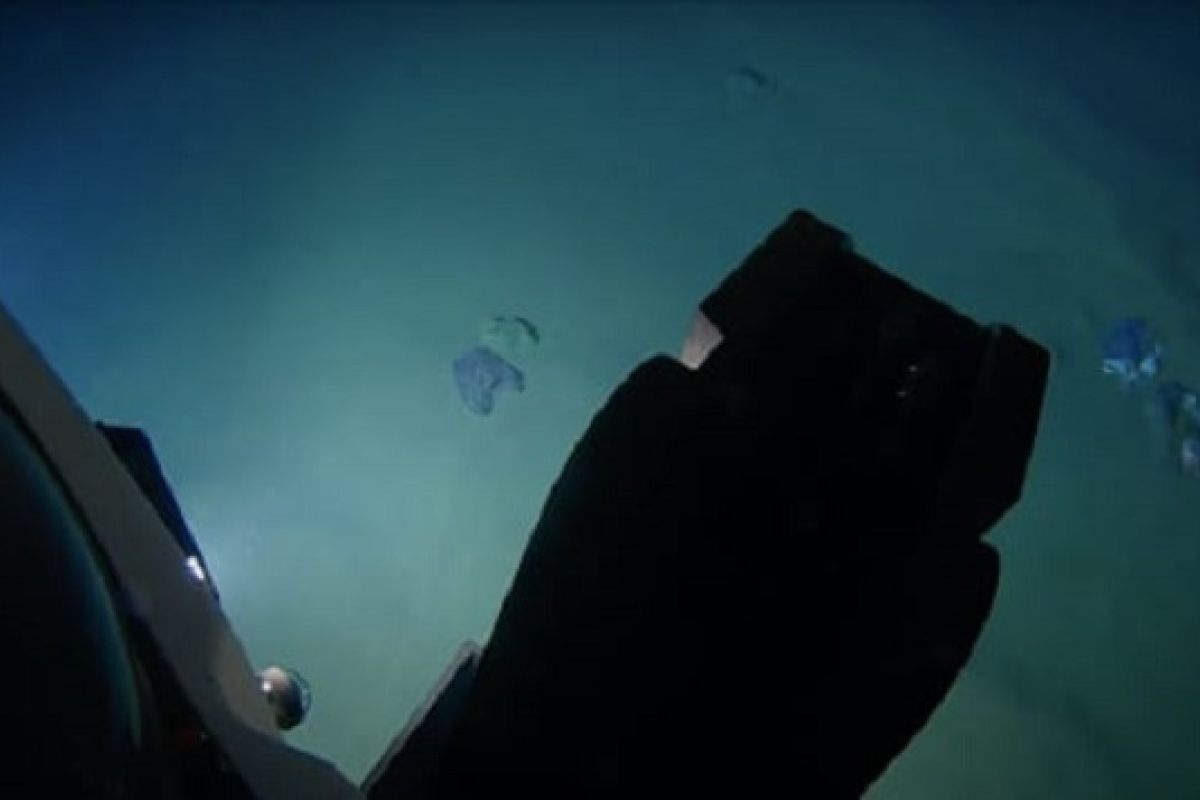

Both he and Onda soon saw that more “travelers” had made the deep dive way before they did: Plastic bags and packaging, even clothes, were half-buried in the sediment.

“If in the beginning, I felt like I was on Mars, when I saw the garbage, I thought to myself, ‘Am I in Payatas?’” Onda told the Inquirer, referring to the landfill in Quezon City. “The sight brought me back to the reality that I’m still on Earth.”

The successful mission into the bowels of the Emden Deep on March 23 marked the first-ever deep dive in the Philippine Trench, a unique marine feature east of Mindanao, and the first-ever deep dive below 10,000 meters within Philippine waters.

While the expedition led by Caladan Oceanic, a private organization dedicated to advancing undersea technology, was not considered a marine scientific research activity, the explorers’ shocking discovery highlighted the worrying extent and impact of human activities on the planet.

Patches of garbage

Onda, an associate professor at the University of the Philippines’ Marine Science Institute, said they began to catch glimpses of the trench’s bottom around four hours after their descent.

It was like an oceanographer’s book come to reality, watching science unfold before his eyes.

At a depth that is deeper than Mt. Everest is high, the Emden Deep appeared like a “ghost town,” he said, with sediments slowly floating away from them.

But as they explored the western wall of the trench, plastic bags, food packaging, even a pair of pants and shirts, would appear every five minutes or so.

“What I was expecting, because of the depth and high pressure there, were fragments of plastic. But they were so intact as if they just came from the supermarket,” Onda recalled.

Vescovo, the first to complete all deep dives in the five deepest points on the planet, said the human debris in the Emden Deep was “pretty extensive.”

“The greatest amount of contamination I’ve seen in any deep dive was at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, at the Calypso Deep, but the Emden Deep is the second largest,” he told the Inquirer. “In the Emden Deep, we saw scattered locations of human debris, isolated here and there. It was in pockets.”

The American explorer noted that materials do not degrade in the deep parts of the ocean, where there is no oxygen and sunlight. “People think that if they throw something into the ocean, it will just decompose over time.”

“But they are actually preserved,” he said.

From Hawaii, Pacific Islands

It remains unclear how the debris made its way to the Emden Deep. With the ocean currents, some of it could have drifted from Hawaii and other Pacific Islands, or coastal communities near the Philippine Trench such as Siargao Island, Onda said.

The garbage may also be from passing ships, with the Philippines near the world’s major shipping lanes, Vescovo noted.

Their discovery, however, underscored the connectivity not only of the world’s oceans, but also of any human activity to the planet, said Onda.

“The Philippine Trench is already so deep, but human pollution was still able to reach it. What more for shallower environments like coral reefs and seagrass beds?” he said. “[If we don’t do anything], I wouldn’t be surprised if I would get confused if I was in the Philippine Trench or in Manila Bay.”

While the expedition opened new scientific questions for him to pursue, Onda, a founding member of the Plastics Research Network, hoped that their worrying discovery would result in more stringent policies, not just on plastic use and waste management, but also on plastic production.

“We don’t expect the plastic problem to go away overnight,” he said. “But hopefully our stories will lead to behavioral change, with people seeing their connection to the problem.”

Oceans should not be seen as dumps for human waste, said Onda and Vescovo.

“Whatever we do will have an impact on our environment,” Onda said. “I hope what we’ve seen will be an inspiration for us to do something about the problem and in our own ways, contribute to the solution.”

The story, previously published by Philippine Daily Inquirer, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021 to highlight critical role of journalism in providing trustworthy news and information for humanity.

#JournalismMatters

Reporter: Jhesset O Enano

Editor: Yuni Arisandy Sinaga

Copyright © ANTARA 2021