As a young member of the customary community, she understands that preserving the Namblong tongue means saving her tribe from extinction.

"Maybe, in 2030, there will be no more Namblong tribe language because currently, the number of speakers is only 20 percent of our tribe's population, and they are older adults," she said during a discussion at the Injo Yamo Community Learning Center on February 9, 2025.

"Injo yamo" in Namblong translates to "cultural school" in Indonesian. Initiated by the Namblong Tribe's Indigenous Women's Movement Organization (ORPA) under the guidance of Rosita Tecuari, 42, the center is located in Benyom Customary Village, Nimboran, Jayapura, Papua.

The non-formal school with 40 students, aged four to 15, is striving to serve as a link across generations to pass on the diversity of cultures to the younger generation of the Namblong tribe.

Hembring is carrying out her mission to introduce the Namblong language to the younger generation in unique ways. One of them is involving speakers in the process of weaving traditional Papuan bags called noken.

For the high school graduate, the process of making noken from orchid fibers involves the use of several Namblong phrases that can be passed on to the younger generation.

"When we gather to make noken, we can learn the language; starting from the selection of materials from plants to the knots of the noken ties," she explained.

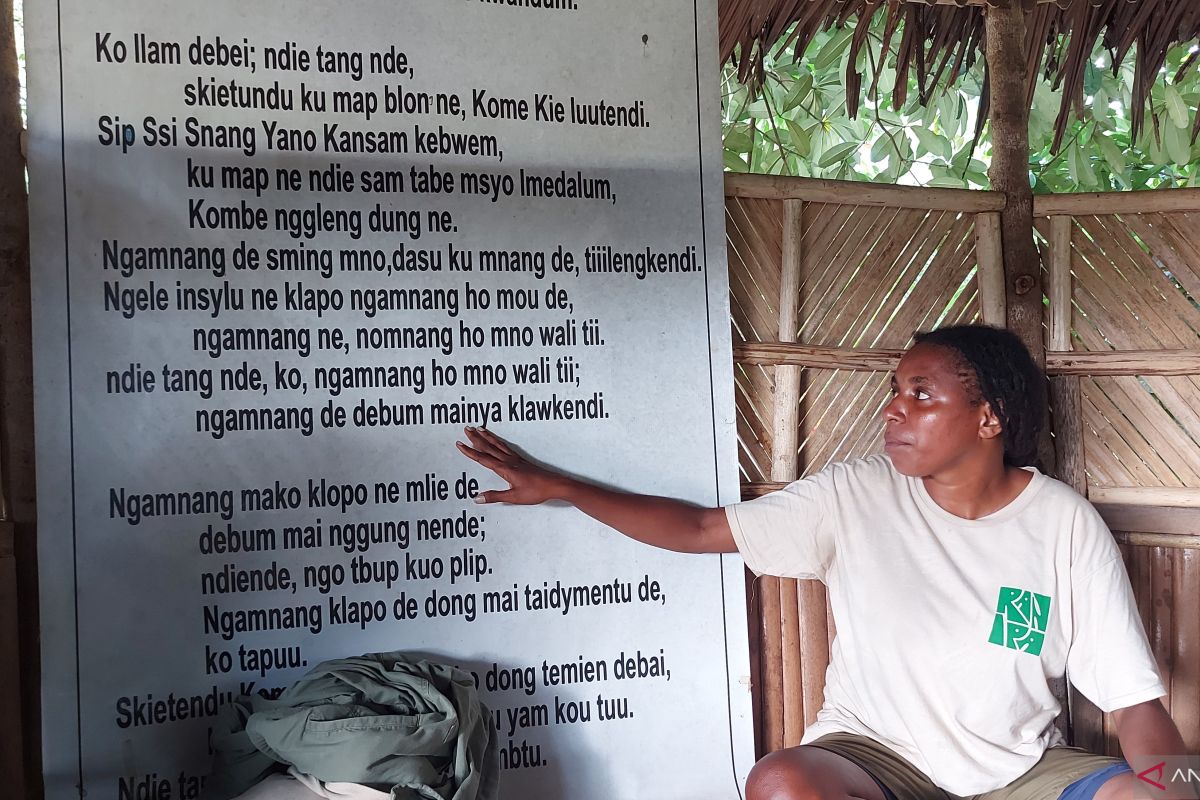

In addition to noken, the transfer of language is also being carried out through poetry and songs, such as the song entitled Nyanyian Burung Cendrawasih sung by Hembring with the following lyrics:

Yu ngali nombe sip

Kande map ho notadetum

Nombe sup

Nombe imum pong de takwap tnag

Nombe nmbuo tasing de

O yu ngali sya pliptyatam.

The lyrics mean "Where do the Birds of Paradise reside, whose beauty graces, whose look is exquisite, whose voices are heard, the Birds of Paradise."

Loss of speakers

At the Injo Yamo customary school, Tecuari welcomes her students with warmth, her face radiating the wisdom of a woman who has long maintained the Namblong tradition.

A noken bag is slung over her shoulder. It usually contains betel quid or personal belongings.

The walls of the classroom are made of wood and woven bamboo. Sunlight streaming in through the gaps leaves patterned shadows on the 5x4 meter terrace. In the middle of the building, a large tree stands firmly.

There, Mama Rosita, as she is usually called, tells stories about the Namblong language and culture that must be preserved. Every word spoken is like a thread that weaves together old memories.

One such memory is related to the Military Operations Area (DOM) policy implemented in Papua from 1978 to 1998. The period triggered extreme fear among people, including the people of Namblong.

Aimed at suppressing separatist movements, the military operations often resulted in certain officers adopting repressive attitudes toward civilians, including the people of tribes.

To survive, Tecuari said, many members of the tribes began to abandon their native language and switch to the more dominant Indonesian language.

Related news: Preserving Kamoro, Amugme languages in digital age

Children of tribes who were born and raised in repressive conditions were taught more Indonesian as part of a survival strategy, considering that certain cultural identities could be considered a form of resistance against the state.

"During the DOM, parents who could not speak Indonesian were forced to use standard Indonesian. If not, they were beaten with gunstock. So how could they possibly teach our customary language to their children?" she said.

The dominance of the Indonesian language in assimilation and education policies triggered the decline of the Namblong language. Children of the tribe were no longer taught their mother tongue, making the younger generation more fluent in Indonesian or even other regional languages than their own.

According to Tecuari, those born in the 80s still understand Namblong, though they cannot use it actively.

During the early 2000s, the influence of other languages became stronger among the Namblong people.

In fact, more and more young people became more familiar with the Javanese language than their own language. This was due to transmigration and wider social interaction with other communities.

Now, with the development of the region and the influx of transmigration residents, the Namblong tribe of Papua is becoming harder to trace. So far, there has been no concrete data on the exact number of remaining Namblong tribe members.

Tecuari noted that the Namblong people are spread over 32 villages in three sub-districts. However, the number of villages where the Namblong people live is declining.

Language preservation

In addition to Namblong, other languages in Papua are also at risk of extinction.

Based on research conducted by the Papua Language Center from 2006 to 2019, four regional languages have been officially declared extinct: the Tandia language, the Air Matoa language, the Mapia language, and the Mawes language (Sarmi District).

Of the four, the Air Matoa language was the last to go extinct. In 2010, research found that only one speaker—an older adult—remained.

Meanwhile, of the total 428 regional languages in Papua, only two have more than a thousand speakers, namely the Dani language of Papua Pegunungan and the Mee language of Central Papua.

The Papua Language Center, in collaboration with speakers of the customary language, has prepared a Namblong language textbook so that students can learn their mother tongue from an early age.

This was confirmed by the principal of Tab Byab Early Childhood Education School of Jayapura, Debora Hembring. The book was compiled in 2013 with the involvement of Australian language experts based on materials gathered from native speakers.

The book was introduced to the school's students in 2015. Namblong language lessons are taught every Thursday and involve pronunciation lessons and singing.

Namblong is also taught at Inpres Imsar Public Elementary School, located 1 kilometer away from the Tab Byab Early Childhood Education School.

One of the students, Judita, said that is it hard to form a sentence using Namblong language. She also finds it easier to pronounce Indonesian words.

In addition, the limited number of textbooks is also a major barrier in the process of teaching local languages. To this end, local governments need to print books in sufficient quantities and involve native speakers so that language teaching can be carried out effectively.

Without concrete steps, more regional languages in Papua will become extinct. Therefore, support from the government, academics, and communities is necessary to keep regional languages alive and passed on to future generations.

Related news: Language center revitalizes local languages in Papua

Editor: Rahmad Nasution

Copyright © ANTARA 2025