As a result, Indonesians are well-acquainted with the dangers posed by such disasters, especially those related to megathrust activity.

A megathrust earthquake is an extremely powerful seismic event that occurs in a subduction zone, which is a region where one of the earth's tectonic plates is forced beneath another.

Although the two plates continue to move toward one another, they become trapped at their point of contact, leading to a buildup of strain that surpasses the friction between them.

A megathrust earthquake has the potential to generate a tsunami due to the significant thrust movement that creates a substantial vertical displacement on the ocean floor.

This movement displaces a large volume of water, which can lead to the formation of a tsunami as it radiates away from the underwater disturbance.

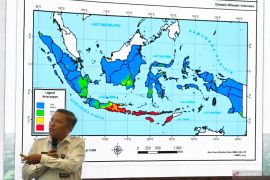

Indonesia has several subduction zones that stretch from the tip of Sumatra Island to Papua.

The latest research conducted by the National Earthquake Study Center (PuSGen) team in 2017 found that Indonesia is surrounded by 13 megathrust zones, comprising the Sunda Strait megathrust zone, which partly stretches from southern Java to Bali, the Mentawai-Siberut segment in western Sumatra, the East Nusa Tenggara segment, West Nusa Tenggara, the northern Sulawesi segment, and northern Papua.

Director of the Earthquake and Tsunami Center of the Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) Daryono stated that of the 13 megathrust zone segments, the government is focusing on the Sunda Strait and Mentawai-Siberut segments. Both segments have the potential for earthquakes with enormous power, endangering the safety of residents.

The Mentawai-Siberut segment in western Sumatra has the potential to trigger an earthquake with a magnitude of up to 9.0 with a tsunami wave of more than 10 meters. A similar warning also applies to the Sunda Strait segment that stretches between Java and Sumatra.

Community resilience

To anticipate the danger, mitigation is necessary to reduce the risk of the impact caused by this megathrust earthquake and tsunami, such as by utilizing modern technology to detect potential dangers and also strengthening community readiness through a series of training, rescue, or evacuation specifications, and ensuring earthquake-resistant building structures.

Indonesia has made significant strides in enhancing its readiness for earthquakes and tsunamis by leveraging modern technology for early detection and warning systems, as well as by empowering communities through lessons learned from past disasters.

The Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami that devastated Aceh in 2004 was a turning point in Indonesia’s disaster mitigation.

The earthquake, with more than 9.0 magnitude that triggered a 20-meter tsunami wave, claimed the lives of more than 170 thousand Aceh residents.

According to the Center for State Budget Policy of the Finance Ministry, the incident caused losses of Rp51.4 trillion (USD3 billion).

Indonesia also continues to improve its early warning system with the support of several countries, including Japan, Germany, and France. It took four years for Indonesia to have an early warning system based on this sensor technology. The Indonesia Early Warning System (Ina-TEWS) was officially operated in 2008.

Currently, Indonesia has 600 seismic sensor units, 240 tide gauge units, and 36 Automatic Weather Station (AWS) units. These tools are installed in several areas, especially those prone to earthquakes and tsunamis.

Ina-TEWS, which is based on seismic-tide guide sensors, has been the backbone of earthquake-tsunami mitigation efforts to date.

This system gives early warning of potential tsunamis in a short time, around three minutes after the earthquake occurs.

Early warning information regarding disaster hazards can be disseminated in real time via the Internet, television broadcast transmitters, and radio services managed by the Ministry of Telecommunications and Digital (Komdigi).

The promptness of this information delivery is deemed adequate to provide communities with a valuable opportunity to evacuate.

During an international tsunami symposium involving global seismology experts in Aceh Province, Head of BMKG Dwikorita Karnawati emphasized the urgent need for Indonesia to acquire underwater sensor equipment capable of accurately detecting potential tsunamis triggered by seismic events, such as earthquakes, and non-seismic activities, such as sea volcanoes.

Karnawati noted that the current hundreds of sensor units in Indonesia are primarily limited to detecting tsunamis caused by seismic activity and lack the accuracy needed to identify those triggered by non-seismic events.

The eruption of Mount Anak Krakatau in 2018 was a reminder of the potential danger of tsunamis triggered by this non-seismic activity. At that time, a five-meter-high tsunami came without an early warning and hit the coast of Banten and Lampung provinces, killing more than 400 people.

Eight years ago, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake hit Mentawai, West Sumatra, causing a tsunami with waves reaching three to 10 meters in height. This event should be a cause for concern, particularly following the identification of a megathrust zone in Mentawai-Siberut that could potentially lead to a larger earthquake exceeding 8.9 in magnitude.

All this modern technology should be accompanied by community preparedness and awareness, especially for those directly exposed to potential dangers. The National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) also emphasized that the formation of a disaster-resilient community is a crucial step.

The BNPB has recorded that more than 53 thousand villages in Indonesia are located in disaster-prone areas. A total of 45,977 villages are located in earthquake-prone areas, 5,744 villages situated in tsunami-prone areas, and 2,160 villages at risk of volcanic eruptions. The population residing in these disaster-prone areas is estimated at 51 million families.

The villages are spread from Aceh, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, Bengkulu, Lampung, Banten, the southern part of West Java, the southern part of East Java, the eastern part of South Kalimantan, Bali, West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, North Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi-Palu, South Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, and North Maluku to South Maluku, and Papua.

With this condition, Indonesia faces a major challenge in educating and building community preparedness.

Based on the latest data, only 36 thousand villages are verified as disaster-resilient. This figure is still far from sufficient to secure all disaster-prone areas.

Disaster resilient villages (Destana) are a mainstay program to increase community preparedness in facing the threats of earthquakes and tsunamis. It includes a series of risk management training, independent evacuation, provision of emergency facilities and infrastructure, and the preparation of evacuation routes along with maps and directions.

The role of Destana can be improved with the provision of earthquake-resistant housing, evacuation shelters, and enforcement of strict regulations on the development of residential areas and tourist destinations in coastal areas.

According to expert studies, if an earthquake lasts more than 30 seconds, there is a 75 percent likelihood of a subsequent tsunami. The characteristics of a tsunami can be observed through the retreat of seawater or the cessation of wind gusts.

Hence, modern technology for disaster detection is necessary and must be accompanied by increasing community awareness and resilience. All these efforts aim to build sustainable development amid the threat of disasters.

Related news: Indonesia's emergency team for Vanuatu to work for one month: BNPB

Related news: Remembering Aceh tsunami: Conserving mangroves to prevent tragedies

Editor: Rahmad Nasution

Copyright © ANTARA 2024