It was once said that not all heroes wear capes. In this case, not all heroes have military rank stars or were essentially called heroes. Some stood up for the cause of a small group of people around them and fought for the rights of the less fortunate and intimidated.

One of them is a man whose name may not be familiar on the national scale, but in the early 1900s, he was once the chief figure for those rebelling against the Dutch colonials. He was known as Entong Gendut and his real name was never really discovered, at least in the documentations that featured his story.

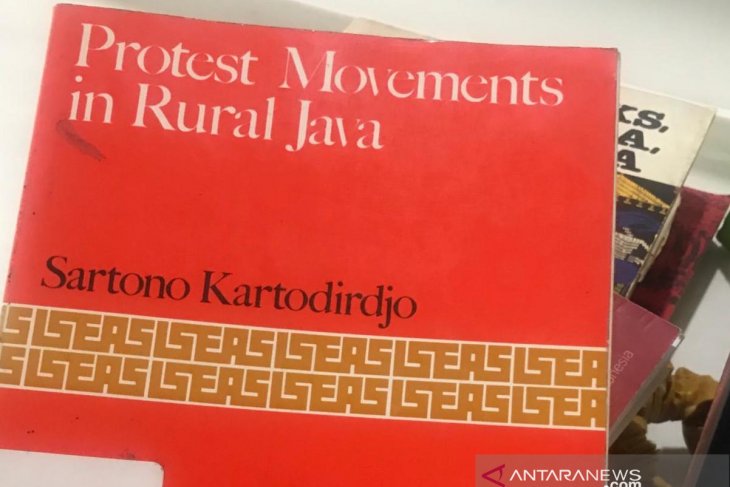

In a book, titled ”Protest Movements in Rural Java,” an Indonesian historian -- the late Sartono Kartodirojo -- brought to life Entong Gendut’s fight against landlords and colonies through a series of stories on protests of farmers in Java in the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century.

“Peasants had to suffer the repeated attempts of landlords to deal with financial difficulties by squeezing the last drop from them and by scaling up the demands made upon cultivators,” Kartodirojo noted in his book, setting the scene of what Entong Gendut was fighting against in the 1916s.

The start of the 20th century was a time of sorrow and despair for local citizens in Batavia called Tjondet, now Condet, as most residents were living as farmers in the lands and plantations owned by landlords. They also lived under exacting taxation policies.

Owing to new-fangled regulations initiated by the landlord, commoners were facing numerous lawsuits and were on the brink of bankruptcy since their properties had been confiscated and sold. These properties were often also scorched.

The displacement of commoners led to distress, resentment and ultimately, restlessness, among the people. Kartodirojo quoted Entong Gendut as saying that he regretted the burning down of houses since the owners were unable to pay their debt.

The fury and resentment that had raged on among the people of Tjondet was ultimately manifested in the rebel movement led by Entong Gendut.

Their first act was conducted in a colonial court, or a landraad, where the court ruled to sue a farmer named Taba to pay fines of 7.20 gulden to the landlord in February 1916. Taba was told to abide by the rules, else his belongings will be seized. Thereafter, Entong Gendut and his entourage voiced sarcastic and insulting shouts, although it did not escalate to further turbulence.

The second action took place on April 15, 1916, in front of Villa Nova that belonged to a European landlord named Lady Rollinson, who owned a vast land in Tjililitan. Entong Gendut and his entourage began their rebel acts by hurling rocks at the car of a Tanjung Oost, now Jatinegara, landlord named Ament, who were headed to the Lady’s Villa for a party.

They then went to the party and managed to sabotage and get the guests to leave, putting an early end to the party.

The last act sent Entong Gendut to the wanted list of the authorities in Batavia. Orders were sent out to capture him.

Not long after the Villa Nova incident, an administrator from the area of Meester Cornelis and the Dutch authorities had surrounded Entong Gendut’s house in Batuampar. Bearing a long, sharp object, Kartidirojo suspected as a spear, as well as a creese, and a red flag adorned with a white crescent on his wall, he proclaimed himself as a young king. The fight led to the administrator being held captive and with that, increasingly more number of authorities thronged the location.

Several rebels fled, while Entong Gendut was shot dead and said to have died later while being taken to the military hospital in Batavia, as revealed by Kartidirojo.

Modern Depiction

His courage and advocacy for those who were intimidated made Entong Gendut a figure worthy of withholding in memory. Though not much information is available on his life in general, documentation regarding his chivalry was projected in a colossal theatre performance in last June by the Museum of Jakarta History in the infamous Old City.

“It was a part of our contribution to the celebration of Jakarta’s anniversary,” Head of the Museum’s Services Galih Hutama Putra stated at the time.

Beyond a doubt, Entong Gendut’s good deeds were worth recollecting. Historian and founder of the Indonesian Historia Community, Asep Kambali, had stated that history is never to be forgotten, as it is the foundation of where the future is headed. It can also serve as a lesson for the current generation to not prevent less than productive events from occurring.

Entong Gendut’s story should perhaps be mirrored in the way the nation cares for its farmers and ensure their welfare and that they are thriving and being protected in the present and future.

Related news: Haji Darip from Klender, a forgotten warlord

Related News: Meet "Si Pitung": Betawi's revered bandit, loathed by the rich

Related News: Reviving the legacy of Sabeni, the Betawi fighter

Related news: Tracking down the hidden Portuguese pearl in north Jakarta

Related news: Indonesians in tunic dresses: Indian descendants in Pasar Baru

Editor: Gusti Nur Cahya Aryani

Copyright © ANTARA 2019