These tariffs impose a baseline 10 percent cost levy on imports into the US from all countries, with additional higher rates applied to specific countries or products based on various factors, including trade surpluses to the US.

Sudden and steep tariffs threaten to force countries to pass more of the costs of their export goods onto US customers, making them more expensive and less competitive.

All ASEAN member states have been threatened with these tariffs, some at excessively high rates. The varying severity of these rates reflects the US' perception of Southeast Asian countries in the context of its rivalry with China, another major trading partner in the region.

Many ASEAN countries face significantly higher tariff rates than, for instance, European Union (EU) states.

The Philippines, the US' main security ally in Southeast Asia, faces the least severe tariffs at 18 percent. Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia – the current ASEAN Chairman – are subject to tariffs ranging from 24 to 25 percent, comparable to those imposed on EU countries.

Indonesia, the so-called ‘de facto ASEAN leader’, whose second-largest trade partner is the US after China, faces 32 percent tariffs.

Lastly, countries with closer political ties to China, such as Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, are threatened with the most severe tariffs, at 45-49 percent.

The varying severity of Trump’s tariffs on ASEAN countries stems from multiple factors beyond trade surpluses.

Most notably, the tariffs appear higher or lower depending on whether the targeted Southeast Asian country maintains comprehensive security relations with the US and its proximity to China, the primary adversary in the US trade war.

Thus, these tariffs undeniably reflect the US perception of Southeast Asia vis-à-vis US-China geopolitical rivalries. The tariffs have already harmed US allies more significantly than they have mere trade partners.

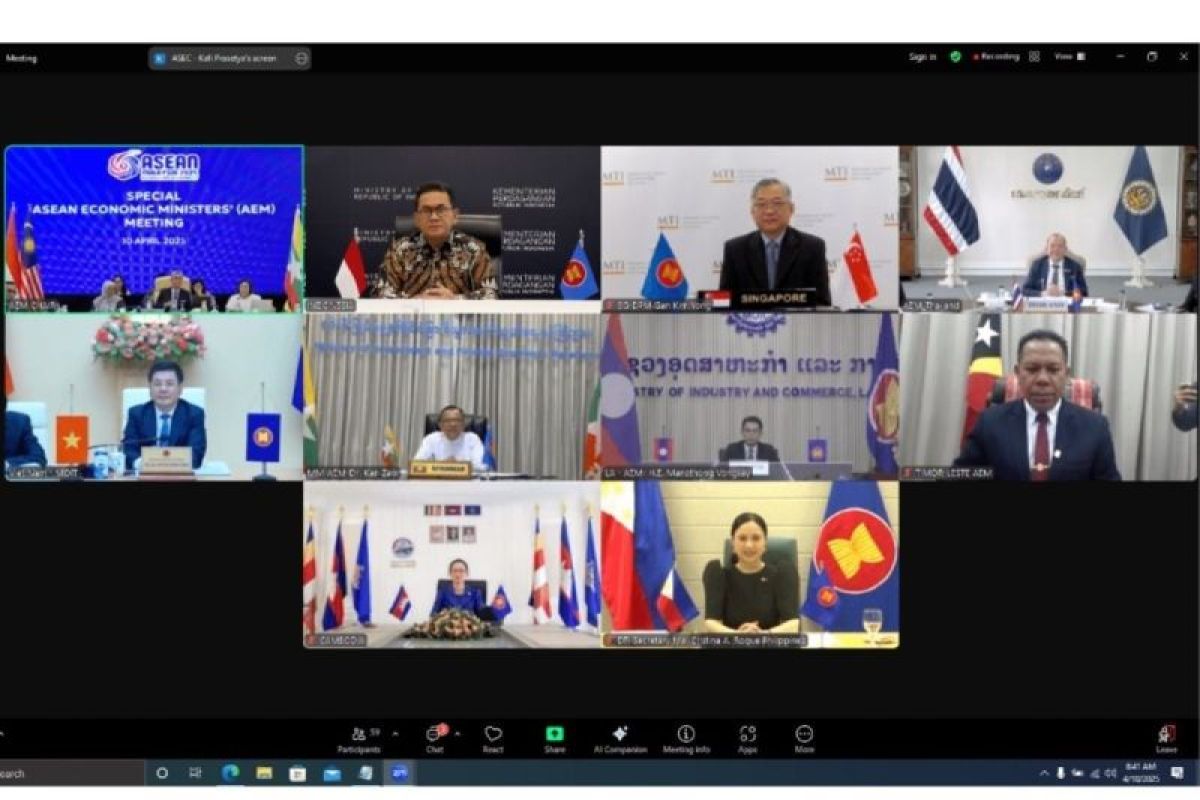

In turn, US tariffs have also affected ASEAN countries, causing them to respond differently. ASEAN members facing tariffs from the same country should encourage coordination on a joint response. In reality, they are struggling to get on the same page.

Among the possible responses by ASEAN countries to these tariffs, the most reasonable approach is a well-planned one that avoids two extremes: escalating a trade war by retaliating with tariffs against the US, or complete US appeasement by offering excessive trade concessions.

The significant difference in economic size between the ASEAN countries and the US makes a trade war unviable.

The disparity in economic sizes also means that an unchecked influx of US goods into an ASEAN country, without stopgaps, will severely harm their domestic industries.

Therefore, ASEAN must avoid engaging in a mismatched battle with an economic giant and being entirely at the mercy of potential trade deficits.

Unfortunately, while countries like Malaysia and Indonesia – the current and recent ASEAN chairs for 2023, respectively – have advocated for joint responses, other ASEAN members have already implemented drastic individual measures.

Vietnam recently offered to eliminate all tariffs on US exports, an appeasement maneuver, only for the proposal to be immediately rejected by the US within two days.

It is evident that any ASEAN country’s isolated response towards Trump’s tariffs is unlikely to sway the superpower from easing its trade policy.

Thus, ASEAN must coordinate its members’ responses to deliver a collective message: that it will not let the region be easily pushed around and will come to the aid of any of its members regardless of the US-China trade and geopolitical rivalries.

A quick glance at ASEAN’s history reveals that the multilateral organization was created to help small Southeast Asian countries navigate crises like the current tariff challenges.

Following the 1950s-60s period of regional conflict in Southeast Asia, the 1967 ASEAN Declaration emphasized economic well-being through sound understanding and meaningful cooperation among – now even beyond – the region.

ASEAN’s establishment entailed an agreement that Southeast Asian countries share responsibility for strengthening the region’s economic and socio-political stability and ensuring peaceful national development for its members.

ASEAN’s ability to manage its proximity to the US and China also demonstrates its potential compared to uncoordinated responses.

Even in the 21st century, ASEAN remains one of the few multilateral organizations besides the United Nations capable of consistently bringing both the US and China to attend talks instead of resorting only to unilateral pressure.

The US and China regularly attend the ASEAN Regional Forum and even the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus, including joint military exercises.

However, Trump’s preference for bilateral negotiations over multilateral talks, not dissimilar to China's approach, will pose a challenge to ASEAN's ability to coordinate a unified response to his tariffs.

Nonetheless, ASEAN’s emblem -- a bundle of padi (rice) stalks -- represents strength through unity, as the stalks are firmer when bound together than when standing alone.

Every ASEAN country stands to benefit from presenting a united front against US tariffs and must demonstrate a willingness to strengthen one another as a collective to withstand the challenges of an impending trade war.

*) Rifqy Tenribali Eshanasir is a Master of International Law and Diplomacy (Australian National University, Canberra), Bachelor of International Relations and Peace Studies (Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan), and Researcher at the Centre for Peace Conflict and Democracy, Hasanuddin University.

Copyright © ANTARA 2025