To this end, the downstreaming of salt—transforming raw salt into products with higher economic value—has been promoted to strengthen coastal economies.

With its extensive coastline and abundant salt ponds, West Nusa Tenggara (NTB) holds a strategic position to prove that salt offers a promising future.

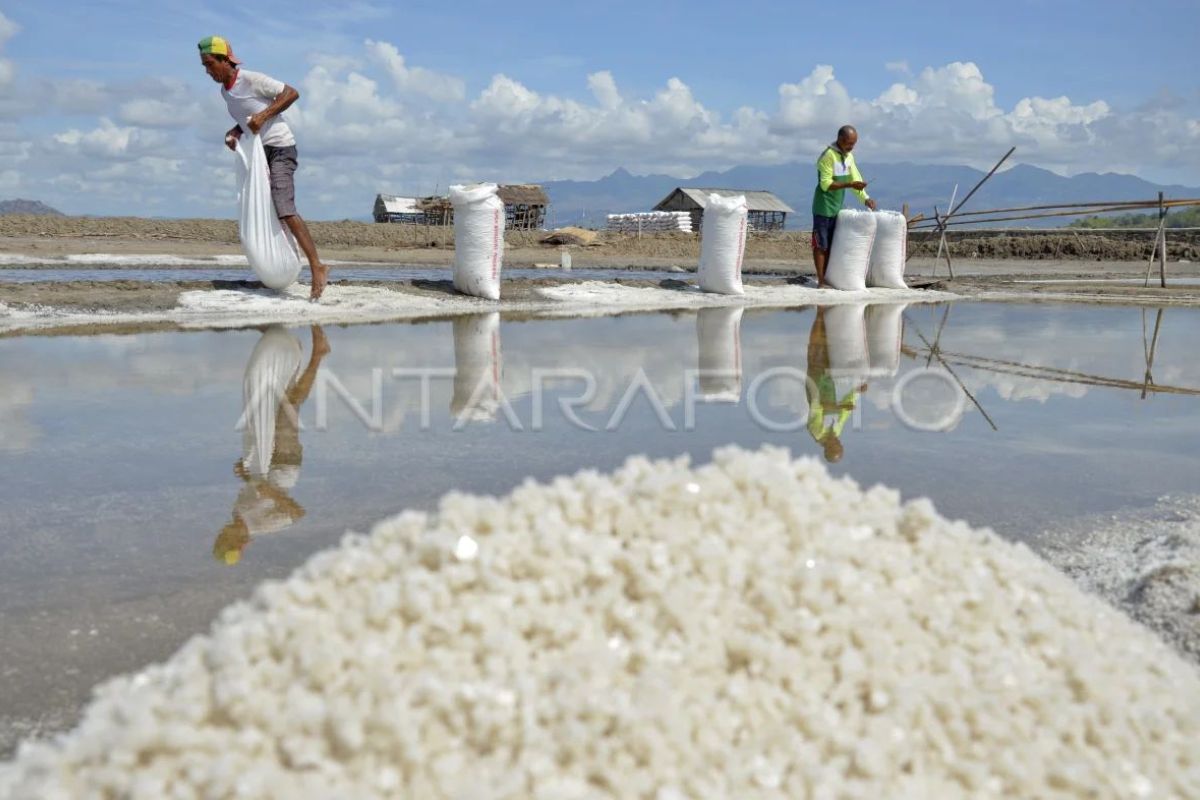

In Bima, Dompu, and East Lombok, coastal communities have long relied on salt as an economic lifeline. However, most of the salt is still sold raw, lowering its economic value.

In recent years, salt downstreaming initiatives have begun to take shape in NTB, marked by the establishment of several processing plants in Bima and Lombok.

Through washing, drying, and packaging, the salt becomes cleaner, more hygienic, and ready to meet industrial standards.

The use of technology in these processes not only improves quality but also raises selling prices, enabling farmers to earn better incomes.

Yet downstreaming is more than technology. It requires building an integrated industrial ecosystem from upstream to downstream.

Without quality raw materials from local ponds, factories struggle to produce goods that meet industrial needs.

Similarly, without efficient distribution networks, processed salt cannot reach markets on time. Downstreaming, therefore, demands a thorough transformation in both production and commerce.

Related news: Indonesia opens investment for National Salt Hub in Rote Ndao

Production and demand

Despite progress, a significant gap remains between production and demand. Production capacity is still limited, distribution chains are poorly structured, and the quality of salt from small-scale farmers varies.

Nationally, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries projects that raw salt demand in 2025 will reach 4.9 million tons, the same as the previous year. In 2023, demand was slightly higher at around 5 million tons, with more than 3 million tons absorbed by the industrial sector.

On the supply side, the 2025 national plan estimates salt production at 2.25 million tons, with reserves of about 836 thousand tons—meeting only around 63 percent of demand.

In 2024, production stood at 2.04 million tons, surpassing the 2 million-ton target.

From this total, NTB’s contribution in 2025 is projected at 180 thousand tons, higher than 150 thousand tons in 2024 and 140 thousand tons in 2023.

Although increasing, the volume still falls far short of national demand, underscoring Indonesia’s continued dependence on imports.

In this regard, salt downstreaming must serve as a bridge. With proper processing, NTB’s salt could enter the food and pharmaceutical industries—or even reach export markets.

Still, the road to self-sufficiency is long. Persistent challenges such as raw material quality, access to capital, human resource limitations, and business practices must be addressed.

Without serious attention, NTB’s vast potential risks being underutilized.

Environmental factors also play a role. Climate change disrupts harvest seasons, with shortened dry periods or early rains reducing pond yields.

Poor land management can further weaken productivity. To stabilize quality and minimize weather-related losses, the use of geomembranes and modern processing technologies is increasingly crucial.

Related news: No rice, salt, sugar, and corn imports in 2025: President

Collaboration

Salt downstreaming is not merely an industrial issue; it has social dimensions.

Enhancing the value of salt through downstreaming not only raises farmers’ incomes but also their dignity.

High-quality salt elevates their role from raw material suppliers to participants in high-value industrial chains.

Success, however, cannot be achieved by one party alone. Collaboration among government, private companies, cooperatives, and farmers is key.

In Bima, for instance, a factory has partnered with farmer groups to secure raw material supplies. In Lombok, geomembrane technology was introduced through a government assistance program.

These examples highlight how technical support, financing, and market access can work together to address gaps in production and quality.

Downstreaming also has implications for human capital. Skilled workers are needed for processing, packaging, and marketing. Training and mentoring for farmers and factory workers serve as long-term investments to ensure NTB’s salt industry can become independent.

With stronger skills, farmers can improve production quality and gain better bargaining power, while factories can deliver consistent, industry-accepted products.

Indonesia’s salt self-sufficiency goal, targeted for 2027, is not just about numbers—it is about the people behind the process.

Every small step today, from pond modernization and cooperative strengthening to human resource development, will shape the future.

In the salt ponds of Bima and Lombok, raw salt is ready to be transformed into high-value products.

With the right support, NTB can emerge as a key driver in achieving salt self-sufficiency while serving as a symbol of the socioeconomic transformation of coastal communities.

Related news: RI Govt highlights NTB potential for salt production

Editor: M Razi Rahman

Copyright © ANTARA 2025