For Indonesian President Joko Widodo, a lockdown is not a better option for controlling the COVID-19 outbreak. Instead, he has vouched for physical distancing.

"Some people have raised questions on why we have not chosen the lockdown policy. I need to say that every country has a different character, culture, and discipline. We didn't choose that path," he stated at the Merdeka Palace, Jakarta, this week, while citing physical distancing was more effective in slowing down transmissions.

"Therefore, the most pertinent way forward for our country is to adopt physical distancing measures. If we can do that, I am certain we can prevent the spread of COVID-19," the President asserted.

Despite the President's strong faith in physical distancing, the number of infections in Indonesia have grown by more than 100 per day.

At last count on Saturday (March 28), the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases stood at 1,155, with 109 new cases reported in the 24 hours since Friday, said Achmad Yurianto, the Indonesian government's spokesperson for COVID-19 handling, in a press conference in Jakarta.

Meanwhile, a few district leaders have begun to shift towards stricter countermeasures in view of public safety. In the city of Tegal, Central Java, Mayor Dedy Yon Supriyono has decided to impose a complete local lockdown for four months, starting March 30, in wake of one of the city’s residents testing positive for the coronavirus. This would be the first such move in the country.

Mayor Dedy Yon Supriyono has said in-and-out access to the city will be closed during the lockdown, and has instructed people to stay at home and avoid any mass gatherings.

“I wish people understand (the need for the lockdown). It’s better me being hated by the people, instead of them losing their lives,” he stated this week.

Before the current outbreak, Indonesia has, over the centuries, endured some of the world's worst epidemics, including cholera in 1821; influenza, part of the Spanish Influenza, in 1918; smallpox in 1965-1967; typhoid in 1846-1850; and plague, or Black Death, in 1910-1914, according to a list compiled by George Childs Kohn in his book Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence From Ancient Times to the Present (Third Edition), published in 2008.

Unlike today, one of the outbreak control policies implemented by the authorities during that time was locking down affected areas.

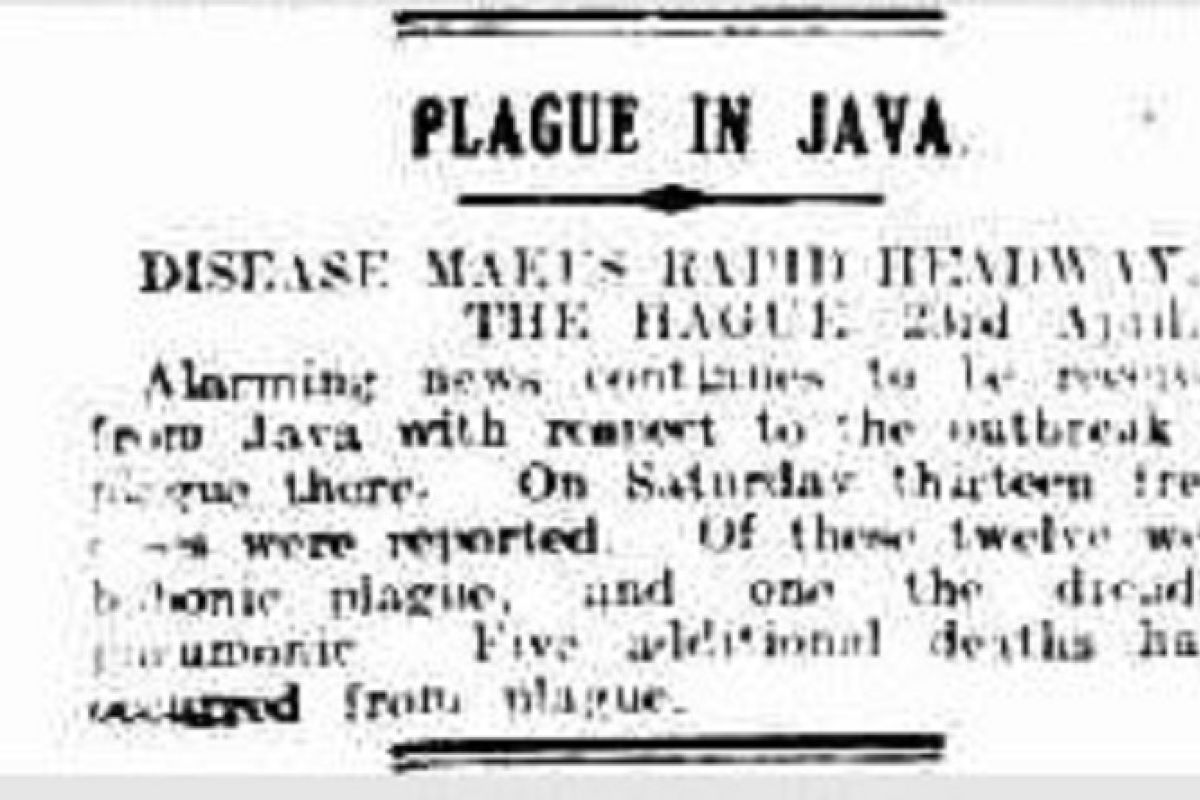

The Javanese plague in 1910-15; 1932-34

The Black Death, or Sampar in Indonesian language, first hit the country in 1910, when a cargo ship transporting rice from Burma (now Myanmar), docked at a port in Surabaya.

“The first cases were noticed in November, 1910 in Turen village, Malang district, (East Java Province), by year’s end, 17 human casualties were reported,” Kohn wrote in his book on the first appearance of plague in Java Island while it was still under Dutch East Indies occupation.

The plague had already ravaged the Central Asia region and European countries since the medieval age (1347 to 1350s). It was named Black Death because “of the black blotches, caused by subcutaneous hemorrhages, that appeared on the skin of diseased human beings near the time of death,” Kohn explained. The disease was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria, with transmission occuring through fleas feeding on infected animals, mostly wild rodents.

A year after the first plague cases appeared in Indonesia, the disease swept across nearly all of the eastern part of Java, and in the next two years, many regions in the western part of the island also reported fresh cases. Between 1913 and 1914, the disease had claimed at least 15,000 lives.

Therefore, to contain its spread, the Dutch East Indies government, who ruled Java Island, formed a joint task force — the Special Plague Service — in 1915. The agency was a combination of local governments, the Civil Medical Service, and the Technical Service.

In addition, the local governments in affected areas also restricted in-and-out access for residents and travelers.

“Travelers in the affected areas were suddenly confronted by roadblocks at all the major intersections (in affected areas), where they and their belongings were forced to submit to disinfection. The findings, which were sent to a laboratory for analysis, revealed presence mainly of common parasites and, very rarely, of rat fleas. The government also ordered the quarantining of victims, evacuation of villagers, and rat–proofing of all houses in the affected areas,” Kohn noted in his book.

“Rat-proofing” roofs involved replacing thatched roofs, which were largely used by Javanese residents, with tiles. “Rafters were redesigned to discourage rats from building nests in them. Trained health workers were sent to live in the village so they could serve as trusted contacts for the local populations,” he added.

Apart from these measures, the authorities also ordered suspected cases to be reported immediately and victims’ funerals to be delayed to allow “a postmortem to confirm the diagnosis,” Kohn highlighted. The burials were also conducted quickly and victims’ families were moved to temporary shelters.

After the measures were put in place, by the end 1915, “East Java’s reported mortality figures were only third of that they had been in 1914”.

Under the Dutch East Indies's occupation, the acute disease hit the island thrice — in 1910-14 (mostly in eastern Java); 1920-1927; and, finally in1932-34 (mainly in western Java). During the final phase in 1934, the number of fatalities “was a staggering 23,239 persons”, because many refused to comply with control and prevention measures imposed by the authority.

Kohn explained many residents in West Java buried plague victims secretly, and that forced the Plague Service to mobilize an intelligence unit to find and report new cases.

The plague in Java gradually disappeared after a mass-inoculation campaign began in January, 1935. “More than two million people were inoculated in that year alone. Over the next few years, several million people were revaccinated,” Kohn stated.

“This new strategy helped slow down and eventually arrest the spread of the disease in Java,” he added.

Related news: Key takeaways from the cholera outbreak that devastated Batavia

Related news: Lessons learned from Indonesia's polio outbreak to defeat coronavirus

Related news: Before coronavirus, the world once fought off smallpox

Editor: Yuni Arisandy Sinaga

Copyright © ANTARA 2020